The deadline for the final say over the new Euro 7 emissions standard is looming. But the debates over the introduction of this new emissions type approval for heavy-duty vehicles (HDVs) is not ceasing. Regulators and environmental groups argue that the new standard is necessary to achieve the European Union’s (EU) environmental and public health objectives. However, the trucking industry contends that the Euro 7 is too expensive and will make it difficult for them to compete amid rising operating costs. Manufacturers also argue that the standard is not necessary, as the industry is already moving towards zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs). Is the Euro 7 proposal more productive or counter-productive in efforts to decarbonize the road transport industry?

The History Behind the Euro Standards

To better understand the debate and criticism of the new Euro 7 standard, it is necessary to look back at the origins and developments of the Euro standards. Over the decades, the EU has implemented a series of increasingly stringent emissions standards for new vehicles.

The first EU-wide emissions standard was formulated all the way back in 1987, with Directive 1988/77/EEC. After several amendments, the Euro I (Roman numerals are typically used for heavy-duty vehicles and Arabic numerals for light-duty vehicles) was finally introduced in 1992.

The Euro I standard required vehicles to be equipped with engines that met certain emissions limits. At the time, these were based on the US Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) emissions standards for heavy-duty trucks. With the introduction of the Euro II in 1996 (Directive 1996/57/EC), legislators required HDVs to be equipped with onboard diagnostic (OBD) systems that monitor engine emissions and performance.

Several years later, Directive 1999/96/EC introduced the Euro III (established in 2000), paving the way for the Euro IV (2005) and Euro V (2008) standards. In addition, it established a voluntary emission standard, known as Enhanced Environmentally Friendly Vehicle (EEV) for extra low emission vehicles.

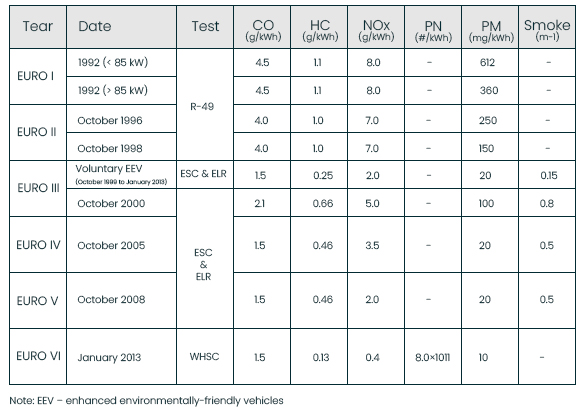

With each revision, stricter limits on pollutants such as nitrogen oxides (NOx), particulate matter (PM), and hydrocarbons (HC) were imposed. However, the requirements and values for each individual pollutant kept changing. Some of the standards (and their amendments) focused on tightening PM limits, others prioritized NOx values, etc.

Throughout the years, crucial additions to the original emissions standards were made as well. For instance, with the Directive 2001/27/EC, the Commission prohibited the use of emission “defeat devices” and “irrational emission control strategies”. Directive 2005/55/EC introduced new durability and OBD provisions with the goal of enhancing diagnostics and repair capabilities of new HDVs.

Beginning with the Euro VI standard, the EU legislation was simplified: directives were replaced by regulations, which are directly applicable (without the need to be transposed into national legislation). Although the Commission first introduced the Euro VI track in 2009, the new standard was (unsurprisingly) only established in 2011, once all the technical details were concluded.

In fact, it took several more years for additional elements for the various implementation steps of the new standard to be introduced. More stringent emission limits became effective from 2013, when the Euro VI finally became applicable to all new diesel and gasoline engines.

Several important elements of the new standard included:

- New testing requirements – including off-cycle (OCE) and in-use (ISC) PEMS (Portable Emissions Measurement System) vehicle testing.

- New transient (World Harmonized Transient Cycle or WHTC) and stationary (World Harmonized Stationary Cycle or WHSC) emission testing cycles.

- Particle number (PN) emission limits (introduced in addition to PM limits).

- Stricter OBD requirements (than Euro IV – V) and even stricter limits on NOx, HC, PM, as well as ammonia (NH3) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) emissions.

EU Emission Standards for HDV Diesel Engines. Source: TransportPolicy.net

Some Euro VI provisions, including off-cycle emissions (OCE) and in-service conformity (ISC) testing, as well as OBD requirements, have been phased-in over several years. The corresponding stages of the emission standards are referred to as Euro VI “A” through Euro VI “E”, the latter being the current stage (since 2021-2022). Unlike in the US, where engine models must be recertified every year, EU type approvals only occur once per emission standard.

The Effect of the Euro Standards

There is no doubt that the introduction of the Euro standards has helped to stimulate the development of new emissions control technologies. For example, the introduction of the Euro 5/V led to the development of diesel particulate filters, which have significantly reduced PM emissions from diesel vehicles. Truck manufacturers have developed a variety of new technologies to meet the increasingly stringent emissions requirements.

Aside of diesel particulate filters, these technologies also include:

- Selective catalytic reduction (SCR) – a technology that reduces NOx emissions from diesel exhaust emissions.

- Exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) – a technology that reduces NOx emissions by recirculating a portion of the exhaust gas back into the engine.

- Turbochargers, which improve engine efficiency and reduce emissions.

One of the most innovative concepts, relevant to current EU polices, was the creation of the EEV standard (1999). According to an article published in Automotive World in 2010 (three years before the full implementation of the Euro VI):

“The EEV standard was intended to create an internationally agreed benchmark which can be adopted by EU member states and air quality conscious urban authorities in establishing truck operator tax-concession incentive schemes and low-emission zone entry rules.”

With the introduction of the Euro VI, EU Member States were offered to use tax incentives to speed up the marketing and early introduction of “cleaner” vehicles meeting the new standards in advance. Incentives were also allowed for scrapping existing vehicles or retrofitting them with emission controls to meet Euro VI emission limits.

Another financial method – discounts on road tolls – were also initiated. Germany was the first to do so with the MAUT motorway road toll reduction scheme, introduced already in 2005. The scheme rewarded operators of vehicles complying with incoming, stricter emission limits than those in force at the time. This helped stimulate the early launch of Euro V trucks.

Is it Time for the Euro 7?

Given the intervals between the introduction of the subsequent Euro standards, it is only fitting that now would be the time for EU legislators to present a new set of emission limits and targets. To further reduce pollutant emissions from all new vehicles within Member States, the Commission put forward the new Euro 7 regulatory proposal in November 2022.

One of the objectives of the proposal is to reduce the complexity of the current Euro emission standards. For the first time, the Euro 7 would bring together the emission objectives for light- and heavy-duty motor vehicles in a single legal act. Until now, these were separated into two different regulations: Regulation (EC) 715/2007 for cars and vans, and Regulation (EC) 595/2009 for buses, trucks and other HDVs.

The Euro standards are one of the key parts of the EU’s strategy to reduce air pollution and improve public health. Thus, the main argument behind the proposed Euro 7 remains largely the same as for its predecessors. Since NOx emissions from both light- and heavy-duty vehicles are a major cause of air pollution, an even more stringent emissions standard would be instrumental in protecting public health and the environment.

According to a 2021 study by the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), the reductions in tailpipe NOx emissions from Euro 7 standard could “prevent 35,000 premature deaths and avoid 568,000 years of life lost over the period 2027-2050”.

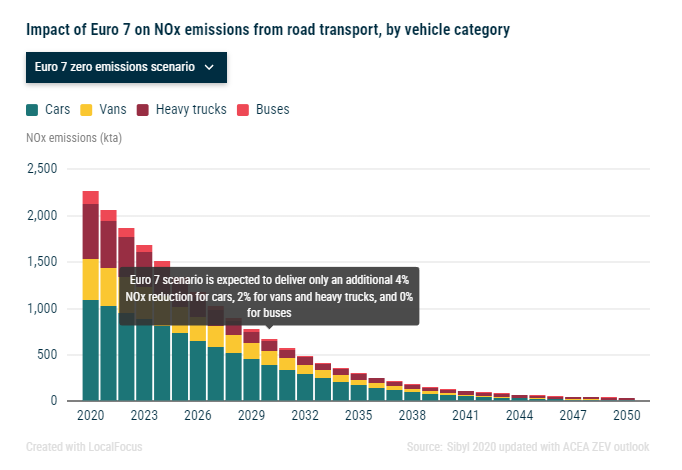

“The analysis found that Euro 7/VII standards will significantly accelerate the reduction in NOx emissions, achieving a 93% reduction in annual emissions by 2050 relative to 2027 (the assumed adoption year of Euro 7/VII standards) compared to a 74% reduction under currently adopted policies. In addition, cumulative NOx emissions over the 2027-2050 period will be reduced by 26% compared to currently adopted policies,” the study by the ICCT reads.

Decarbonizing Europe’s Road Freight Transport

Aside of health objectives, more than ever before, the Euro 7 emission type approval plays into the EU’s environmental objectives and broader ambitions to fight climate change. Regulators have already set out to completely decarbonize the road transport sector by 2050, by introducing CO2 emission targets for new HDVs.

Following the Commission’s proposed revision of the initial (2019) regulation on CO2 emission standards for HDVs, on October 24, 2023, the Environmental Committee of the European Parliament agreed on strengthening the CO2 emissions reduction targets for trucks and buses.

The proposal extends and increases the target levels, requiring manufacturers to reduce the average emissions of new sales by 45% from 2030, by 70% from 2035 and by 90% from 2040 onwards. The revision would also extend the scope of the regulation to cover smaller trucks, urban buses, long-distance buses, and trailers. In addition, all newly registered urban buses should be zero-emission starting 2030.

“The transition towards zero-emission trucks and buses is not only key to meeting our climate targets, but also a crucial driver for cleaner air in our cities. We are providing clarity for one of the major manufacturing industries in Europe and a clear incentive to invest in electrification and hydrogen,” said rapporteur Bas Eickhout in an official press release, adding that „we’re adapting several targets and benchmarks to catch up with reality, as the transition is moving faster than expected.”

Notably, the definition of a “zero-emission heavy-duty vehicle” was amended to lower the proposed threshold for trucks to 3 gCO2/tkm/pkm. What comes next? By June 2024, the Commission is expected to present a legislative proposal with the objective to increase the share of zero-emission trucks (ZETs) owned or leased by large fleet operators, including with binding zero-emission mandates on large fleet operators.

The CO2 emissions reduction targets for trucks and buses are in line with the European Green Deal and “REPowerEU” objectives. And while neither these targets, nor the Euro 7 proposal are part of the “Fit for 55” package, they are closely linked to it. As a set of separate initiatives, they would contribute to the EU’s aim to reduce its net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by at least 55% by 2030 (compared to 1990 levels) and achieve climate neutrality in 2050.

“The Euro 7 regulation sets rules for emissions that supplement the CO2 limits,” the European Council notes in its policy on clean and sustainable mobility. The Euro 7 regulation is part of the Commission’s “2020 Sustainable and Smart Mobility Strategy” and the “2021 Zero-Pollution Action Plan”.

The Main Elements of Euro 7

In latest developments, on September 25, 2023, the Council adopted a “general approach” on the regulation for the new Euro 7 emission type approval, suggesting a number of changes to the Commission’s proposal. Existing emission limits and test conditions for light-duty vehicles remain the same as established in Euro VI. However, in the case of HDVs, emission limits are lower and test conditions slightly adjusted. The Euro 7 also contains a special provision on urban buses to ensure coherence with the 2030 zero-emissions target for these vehicles.

Key elements of the Euro 7 regulation include:

- Introduces limits for “non-exhaust emissions” – particles from brakes and tires. Brake particle emission limits and tire abrasion rate limits are aligned with international standards adopted by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe.

- Sets minimum performance requirements for battery durability in electric cars and stricter vehicle lifetime requirements.

- Provides for the use of advanced technologies and emission-monitoring tools.

According to a new study by the ICCT, the newly proposed Euro 7 emission limits could prevent around 1 million tonnes of NOx emissions and avoid 7,200 premature deaths linked to these emissions in Europe by 2050. The majority (77%) of the emissions reductions would come from trucks and buses.

If adopted as currently proposed, the ICCT assesses, Euro 7 standard would be introduced in 2025 for light-duty vehicles, impacting around 58 million new cars sold through 2035; and introduced in 2027 for HDVs, affecting a projected 3 million new trucks and buses that will be sold through 2050.

Source: ICCT

There is also the possibility of a gradual, delayed implementation of Euro 7 emission standard. One idea is to enforce Euro 7 for cars and vans three years after the entry into force of the regulation and five years after for trucks and buses. Assuming Euro 7 standards are adopted in 2024, this proposal would see the standards taking effect in 2027 for light-duty vehicles and 2029 for HDVs.

The Cost of Euro 7

The Euro 7 regulation is currently under discussion in the European Parliament and the Council of the EU but faces opposition from certain political groups. However, pushback is not something that regulators are experiencing with the Euro 7 only. Although the Euro standards did fuel innovation in the automotive industry, the progress towards a more environmentally friendly road transport industry did come with its set of challenges.

Earlier rounds of the EU’s emissions standards had been widely criticized by manufacturers. The main issue was the EU legislators’ procrastination in setting the deadlines for compliance with the new and changing emissions limits, as explored earlier. As a result, manufacturers were forced to come up with technological breakthroughs in rushed development and production programmes and faced many compliance problems.

The dilemma today arises from the fact that European car manufacturers have already set their sights on and are currently undergoing a transformation towards the production of zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs) and low-emission vehicles (LEVs). Because of that, manufacturers and the trucking industry argue that the proposed standard is simply not necessary.

The road freight transport industry claims that the cost of complying with the Euro 7 would be a significant financial burden for truck operators, who are already facing rising costs due to various factors. The proposed standard would require HDVs to be equipped with new emissions control technologies that are not yet widely available. This could lead to supply chain disruptions and delays in the delivery of new HDVs.

In response to the Council’s position, the European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA), called the revision of the Commission’s proposal “a step in the right direction”, but said that it “still falls short”.

“The member states’ position is an improvement on the European Commission’s Euro 7 proposal – which was entirely disproportionate, driving high costs for industry and customers, with limited environmental benefits,” stated ACEA Director General, Sigrid de Vries in a press release. “The Council’s aim to continue the effective Euro 6/VI tests is sensible. However, compared to what is in place today, Euro 7 is much broader for new cars, vans and, in particular, heavy-duty vehicles, requiring significant engineering and testing efforts. As such, it will require huge additional investments from our industry at a time when it is pouring all its resources into decarbonisation,” added de Vries.

According to ACEA’s analysis, the direct costs of implementing Euro 7 would be four to ten times higher than the Commission estimates in its Euro 7 impact assessment. The organization points to a study by Frontier Economics, which concluded that the average incremental direct costs of Euro 7 vehicles (compared to Euro 6/VI) are largely driven by equipment and investment costs and are about €2,000 for cars and vans with an internal combustion engine, and €12,000 for diesel trucks and buses.

Source: ACEA

The study also states that the Euro 7 proposal would also lead to indirect costs, such as higher fuel consumption. Over a vehicle’s lifetime, this could increase fuel costs by 3.5% (an additional €20,000 for long-haul trucks and €650 for cars and vans). These indirect costs would add to the total cost of owning a vehicle (TCO), placing additional financial pressures on both consumers and businesses at a time of high inflation and economic uncertainty.

The Issue with Fleet Renewal

Coming back to the 2021 study by the ICCT, the organization agrees that increasing the level of electrification would help further reduce emissions, but only to a point.

“If 100% sales shares of zero-emission vehicles for light-duty and heavy-duty vehicles are reached by 2035 and 2040, respectively, cumulative NOx emissions over the same period will be reduced by an additional 5% points,” the analysis reads.

According to the ICCT, unless the adopted policies are revised to aim for a more “ambitious” ZEV uptake scenario, the current strategies would, in fact, achieve less in terms of emissions reductions (and associated health benefits) than implementing Euro 7 standard solely, without a widespread rollout of ZEVs.

“Heavy-duty vehicles will benefit proportionately more from Euro 7/VII standards as even achieving 100% zero-emission vehicle sales by 2040, nearly a quarter of the heavy-duty stock will remain powered by an internal combustion engine powertrain by 2050. Compared to currently adopted policies, cumulative NOx emissions from heavy-duty vehicles over the 2027-2050 period are reduced by 37% under Euro 7/VII, compared to 20% for light-duty vehicles,” the ICCT report continues.

While both the ICCT and ACEA agree that internal combustion engines are here to stay, ACEA maintains that under the current Euro 6/VI standards, the Euro 7 is actually “unlikely to make much more of an impact”. The organization points out that the Euro 6/VI is the most stringent emissions standard to date and has, so far, been successful in reducing air pollution from vehicles on EU roads.

According to its analysis, between 2014 and 2020, the Euro 6/VI helped slash the total NOx emissions from cars and vans within the EU by 25%, and by 36% from HDVs. In general, between the first Euro standard and the first version of Euro 6, emissions were cut by over 90%, ACEA estimates. In contrast to the ICCT’s position, the auto manufacturers’ association warns that the new standard may be “counterproductive” and that it is the introduction of the Euro 7, not of ZEVs, that risks slowing down fleet renewal.

ACEA argues that eight years after the implementation of the Euro 6/VI, the full impact of this emission standard is “being held back” by the high proportion of older vehicles still in use: “pre-Euro VI trucks account for three-quarters of the total trucks within the EU and 92% of NOx”. The simple fact is, if operators and eventually, the end consumer, are faced with higher priced vehicles, they will likely be inclined to keep older vehicles for longer.

“The Euro 7 proposal would only reduce road transport NOx emissions by less than 4% for cars and vans (compared to Euro 6 levels) and by about 2% for trucks. But it will entail significant human and financial resources. Without tackling the older vehicles, Euro 7 will have a barely perceptible impact on road transport NOx emissions,” the organization, representing 14 largest European auto manufacturers, states in its fact sheet.

Source: ACEA

While European manufacturers agree with the need to address non-exhaust emissions, as the Euro 7 proposal stipulates, they recommend fleet renewal based on the existing Euro 6/VI technology. ACEA argues that replacing older vehicles with Euro VI models, alongside the rollout of zero- or low-emission vehicles powered by electricity, “would bring an 80% reduction in road transport NOx emissions by 2035 compared to 2020”.

Who Will Carry the Burden?

Recognizing the significant transformation towards electric mobility that the industry is now undergoing, the Council of the EU states that the goal of revising the Euro 7 proposal was “to strike a balance” between stringent emissions requirements and additional investments for the industry.

“Europe is known across the globe for producing low-emission and top-quality cars. Our position is to continue the path of leading the mobility of the future and adopting realistic emissions levels for the vehicles of the next decade while helping our industry make the definitive leap towards clean cars in 2035,” said Héctor Gómez Hernández, Acting Minister for Industry, Trade and Tourism, in a press release announcing the Council’s general approach.

However, manufacturers state that, once again, the burden of the EU’s current emission reduction policies – be it the Euro 7 standard or the proposed CO2 targets for new HDVs – falls entirely on the supply side.

Manufacturers are calling on the European Parliament and the Commission to craft an Euro 7 regulation that would keep vehicles affordable and the sector competitive. At the same time, they insist that more needs to be done in terms of stimulating market demand of ZEVs from customers for a faster and more feasible market uptake of clean vehicles.

Given the high tensions surrounding the debate over the Euro 7, it is likely that the introduction of the new emissions standard will take some time, as regulators attempt to straighten out all the details to meet the varying demands of different interest groups.

Despite that, all these groups agree on one thing: that the internal combustion engine will continue to play a role in certain HDV operations in the long-term. And agreeing on the final Euro 7 regulation may not be as hard of a task as ensuring timely fleet renewal with all the associated costs that will undeniably reach the end consumer.